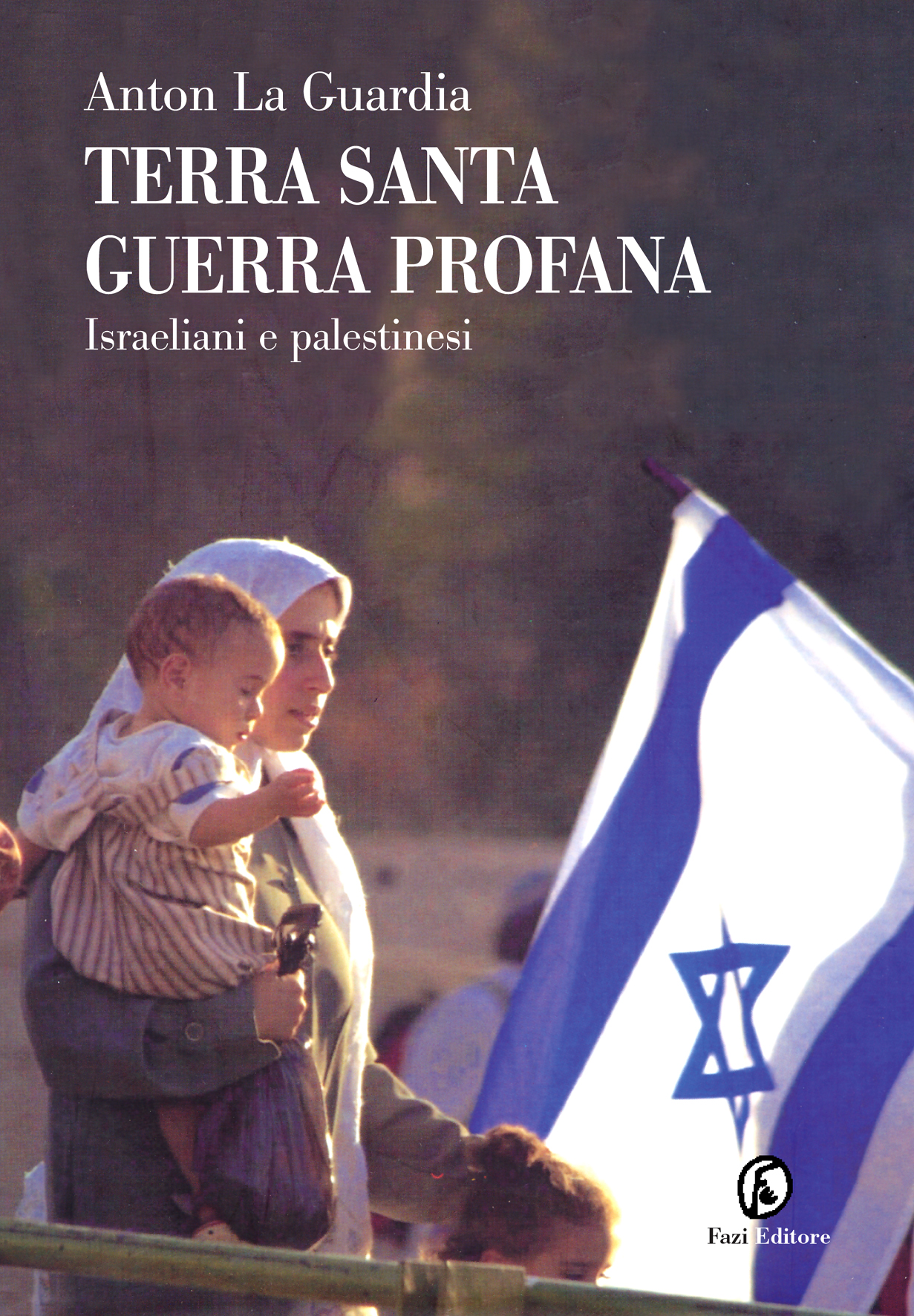

Anton La Guardia

Terra Santa, Guerra Profana

Israeliani e palestinesi

Traduzione di Nazzareno Mataldi

Un approfondito esame storico-politico del conflitto arabo-israeliano, che ricostruisce tutte le tappe che hanno portato alla drammatica situazione odierna. Dall’epopea dei primi pionieri sionisti fino alla disperazione dei kamikaze palestinesi, Anton La Guardia ci racconta la vera storia del rapporto conflittuale tra Israele e Palestina, di come le reciproche promesse di pace siano diventate minacce e quindi realtà di guerra. Scritto nella forma di reportage politico e insieme di saggio storico, Terra Santa, Guerra Profana è uno di quei libri unici, dove la passione civile si lega all’amore per la verità, dove la compassione umana e la volontà di comprendere sono molto più forti di qualsiasi prospettiva di parte.

«Questo libro adempie al difficile compito di non prendere le parti di nessuno, mentre tutti si lasciano trasportare dalle passioni. Leggetelo: la complicata questione israelo-palestinese vi parrà di gran lunga più chiara».

John Simpsons, BBC

– 22/12/2002

Capire la pace

Già corrispondente dal Medioriente per circa dieci anni del giornale britannico “Daily Telegraph”, Anton La Guardia ha cercato nel suo Terra Santa, guerra profana, di riassumere le ragioni e lo sviluppo del conflitto tra israeliani e palestinesi. Riunendo interviste e reportage realizzati sul campo, con un’ampia documentazione d’archivio, La Guardia ha costruito un testo prezioso che, offrendo un quadro esaustivo della vicenda, parla il linguaggio della pace e del dialogo.

– 23/08/2002

La Guardia: il mio viaggio nell’inferno-Medioriente

Raccontare la guerra in Palestina in modo neutrale è davvero arduo, ma Anton La Guardia, gornalista del Daily Telegeraph di origine italiana, corrispondente per anni dal Medio Oriente, ci è riuscito. Il risultato è una ricostruzione storica del conflitto dal progetto sionista di Herzl alla strage di Jenin scritta con la leggerezza del reportage e la sapienza del cronista. L’autore dà voce al dolore e alla rabbia dei due contendenti attraverso testimonianze drammatiche che ci aiutano a dimenticare.

Sharon e Arafat guideranno i loro popoli alla pace o alla guerra?

“La crisi si risolverà a medio termine e non saranno né Sharon né Arafat a risolverla; ormai settantenni; gli israeliani hanno perso fiducia in Arafat e i palestinesi non credono che se se ne liberassero Sharon accetterebbe la nascita dello stato palestinese sui territori che lui stesso ha contribuito a conquistare nel ‘67”.

Le due parti sono pronte ad accettare una pace frettolosa imposta dall’esterno?

“Credo che tutti siano esausti e pronti a un accordo di pace, ma la disillusione accentua gli estremismi; i palestinesi giudicano quella dei kamikaze una forma di lotta legittima, d’altronde, d’altronde in Israele cresce il numero di chi chiede i “trasferimento” dei palestinesi dai territori occupati. Il mondo ha un ruolo cruciale, ma non può imporre un accordo, ci vorrebbe una nuova risoluzione dell’Onu che ripartisse dai parametri posti da Bill Clinton”.

– 04/08/2001

Divided city

There is a fun-ride in Jerusalem, an Israeli equivalent of a Disneyworld attraction. Strapped to chairs, the audience are thrown about as they are whisked through a big-screen, computer-graphic-enhanced account of the city’s past. Queues of children outside are testimony to its popularity; but as a piece of history, it is badly skewed. There is only a fleeting appearance by the Arabs in the 40-minute ride, although they have continuously occupied the city for thousands of years. The impression left is that Jerusalem was and is a Jewish city.

The Israelis and Palestinians, fighting a propaganda war, have two very different versions of history. The Israelis complain, with much justification, that Palestinian textbooks incite violence and are anti-Semitic, but the Israeli version of history is equally dubious. The strength of Anton La Guardia’s book on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is that it attempts to balance these competing histories. He strives to deal fairly with each, but that does not mean he ends up with bland judgments. His verdict on both sides is harsh, though the Israelis probably come off worse.

On the Israeli version of history, especially a tendency to blank out the land-grab of 1948, the year their state was founded, he writes: “The mental delusion whereby a whole people can preserve the memory of biblical events more than 2,000 years old and yet eradicate a centuries-old Arab history from its midst has not yet been given a satisfactory name. Nationalism? Propaganda? Religious blindness? Guilt? It has elements of all of these.” He also criticises the Palestinians, whom he says should be arguing for their rights on moral grounds but instead have often retreated into anti-Semitic rants.

La Guardia was the Middle East correspondent for the Daily Telegraph throughout most of the 1990s, and is now its diplomatic editor. Many journalists covering the Jerusalem beat feel a need to write a book, but Holy Land, Unholy War is more than an end-of-term project. La Guardia spent at least three years researching the book, and interviewed participants on both sides at length. He uses their accounts to personalise the story of the conflict.

He starts where most visitors to Israel begin, with the erratic security arrangements at Ben Gurion airport, and continues along the road to Jerusalem, noting the scenes of past battles. He devotes much of the early part of the book to the Holy City and the competing claims on it by Muslims, Christians and Jews. Of the three, the Christian crusaders behaved the worst on capturing the city, and the Muslims the most humanely.

He covers the origins of Zionism in the 19th century, the steady settlement by Jews in Palestine, and the variety in Israeli society today, ranging from ultra-orthodox to secular Jews. On the Palestinian side, he dispels the convenient European myth that Palestine was almost empty when the Jews began to settle there in earnest in the 19th century. He looks at the founding of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation and all the mistakes and missed opportunities of its leader, Yasser Arafat, and the subsequent rise in the late 1980s of the suicide bombers of Hamas and Islamic Jihad.

The most uncomfortable chapter, “Victims of Victims”, deals with whether it was morally right for European Jews to take this slice of Arab land. In one passage, La Guardia relates the unease of an Israeli who has trouble irrigating an orchard. An Arab appears and tells him how to make the irrigation system work. Asked how he knows, the man answers: “This is my orchard.” He is not likely to get it back. La Guardia says: “If the Jews were victims of the Nazis, the Palestinians are in many ways the victims of the victims.”

Most of the recent outstanding books about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have been either academic, from Israeli historians such as Benny Morris, or works of “fine writing” from authors such as David Grossman. The best by a reporter was generally thought to be Thomas Friedman’s From Beirut to Jerusalem , but that was 12 years ago, and many of its judgments were glib. La Guardia, whose account runs up until June this year, has produced a better book, combining history and news reporting.

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian Newspapers Limited 2002

– 30/06/2002

Territorio sacro

Per chi non sa nulla del conflitto israelo-palestinese, Terra santa, guerra profana è un ottimo punto di partenza. Per quelli che invece hanno già letto tutto al riguardo, il libro di La Guardia, magnificamente scritto, offre nuove e interessantissime chiavi di lettura. Produrre un libro di gradevole lettura che sia anche prezioso dal punto di vista dei contenuti è una grande impresa. Lo scopo di La Guardia è quello di spiegare perché un conflitto che risulta essere distruttivo per entrambe le parti, e in cui nessuna delle due può vincere, non riesce a trovare soluzione. La faccenda è patologica più che diplomatica. Ha a che fare con paura, vendetta, delusione, prepotenza, incompetenza e limiti ineluttabili della geografia. Le opinioni di La Guardia sono molto stimolanti, ma non incoraggianti. E il suo non è un libro per gli ottimisti, se ancora ce ne sono.

La Guardia, giornalista britannico di origini italiane, ha vissuto in Israele per gran parte degli anni ’90 e ha incontrato moltissimi personaggi interessanti, sia ebrei che arabi. Ha parlato con sopravvissuti dell’Olocausto ed ebrei nati nei Kibbutz, le cui opinioni sono ambivalenti riguardo al destino degli ebrei d’Europa. Ha intervistato anziani palestinesi cosmopoliti e lancia-sassi semi-analfabeti dei campi profughi. Narra le storie di poeti, contadini, soldati, musicisti, dottori, fanatici religiosi e laici convinti – tutti apparentemente condannati a vivere come scorpioni in quel barattolo chiamato Terra Santa. Molti di loro, come individui, hanno suscitato la sua ammirazione; come gruppi rivali, invece, li ha trovati egoisti, miopi e persino spregevoli.

La Guardia ha un vero talento nel creare frasi efficaci ed espressive. La buona scrittura è sempre benvenuta, ma in questo caso non è fine a se stessa. La Guardia usa la sua notevole capacità narrativa e stilistica per fare luce sulle due grandi ineluttabili realtà del conflitto: la frammentazione sociale e politica che paralizza la capacità decisionale degli Israeliani, e la rabbia inestinguibile dei palestinesi che finirà col costringere gli ebrei a prendere delle decisioni che la loro società potrebbe non riuscire a sostenere.

L’analisi di La Guardia non accontenterà i sostenitori di Israele. Egli ridimensiona fortemente l’immagine degli ebrei coraggiosi e creativi che costruiscono una società produttiva nel deserto lasciato dagli abitanti sottosviluppati del luogo. Infatti, l’effetto più rilevante di questo libro è la scomoda verità che La Guardia evidenzia sulla situazione palestinese. Chi non riesce a comprendere perché l’Intifada continui, nonostante i colpi di cannone degli israeliani e la virtuosa retorica di Washington, troverà qui tutte le risposte.

La Guardia argomenta in modo convincente perché il conflitto sia ingestibile: una forza inarrestabile – le speranze illusorie da parte dei palestinesi di tornare alle loro antiche dimore – riescono a colpire in grado di colpire uno stato ebraico, talmente fratturato da divisioni religiosi e sociali, da essere incapace di prendere quelle decisioni necessarie a raggiungere la pace, come l’abbandono le colonie del West Bank. Dalla conquista nel 1967, afferma La Guardia, Israele si è lasciato corrompere dalla “mentalità deviata dell’invasore”, ed è ora incapace di liberarsene. Israele non risponde ai lutti palestinesi, perché “teme di perdere quel diritto esclusivo degli ebrei sulla sofferenza”.

Una dura analisi di Israele, ma i palestinesi non ne escono molto meglio. Le loro azioni, infatti, non fanno che rinforzare quelle stesse paure che inducono Israele a reprimerli.

Anton La Guardia ha prodotto un libro forte e illuminante sui popoli che si combattono in Terra Santa, i quali – secondo l’autore – non saranno mai in grado di risolvere da soli il conflitto, ma necessitano di un deciso intervento a livello internazionale.

Per leggere l’articolo nella sua versione integrale, in inglese, clicca qui

Selezione di articoli di Anton La Guardia sul conflitto israelo-palestinese

“Autocratic leader is persuaded by might not right”

DAILY TELEGRAPH – LONDON

27-6-2002

Anton La Guardia, Diplomatic Editor, recalls the Palestinians’ first chaotic exercise in democracy

A portrait of Yasser Arafat hung above the entrance of the Bethlehem school as Palestinian voters lined up to vote to choose their own leader for the first time.

My Palestinian translator flew into a rage and climbed on a chair to take it down.

“This a polling station,” she shouted. “It is illegal to have pictures of candidates.”

A policeman at first tried to stop her showing such disrespect to the “symbol” of the Palestinian struggle. Then he relented and took it down himself. “Never mind,” he said with a smile. “Tomorrow we will put it back up.”

As everyone expected, Mr Arafat was overwhelmingly elected president of the Palestinian Authority.

The last exercise in Palestinian democracy in 1996 was, like Arafat himself, chaotic, flawed and at times absurd. But by the standards of the Arab world it was a reasonably genuine expression of the Palestinian will.

In contrast with other Arab leaders who like to hold fake referendums on their own rule, Mr Arafat had a real challenger: the late campaigner Samiha Khalil.

She predicted that the Oslo accords would not hold and that the only way to prevent more bloodshed was to create a Palestinian state.

Mrs Khalil received minimal coverage in the official Palestinian media, although Israeli journalists lined up for interviews. But she seemed untroubled.

“Arafat is trying his best,” she said. “He believes in the step-by-step approach. I do not. But he is my friend and my president.”

The real contest was for influence in the legislative council, where independents opposed pro-Arafat candidates. The opposition groups – Marxist factions and Islamists opposed to the Oslo accords – eventually boycotted the ballot.

European election observers denounced irregularities. Jimmy Carter spoke of intimidation of human rights activists. But Mr Arafat could not prevent several independents from defeating his candidates. When the legislators managed to pass laws not to his liking, he ignored them.

For example, the Basic Law, a document outlining the powers of Palestinian institutions, gathered dust on Mr Arafat’s desk for years.

This month he signed it into law. It took America’s might and not the clamour of democratically elected Palestinian representatives to change his autocratic ways.

“Arafat escapes his third ‘last stand’ and claims victory”

DAILY TELEGRAPH – LONDON

02/05/2002

ANTON LA GUARDIA on the implications of the ending of the siege of Ramallah

In the mythologised history of the Palestinian revolution, the end of the siege of Yasser Arafat’s headquarters will no doubt be recorded as a great victory.

But it is far from clear, after five weeks of bloody fighting, whether he is any closer to leading his people to the cherished aim of independence.

In material terms, Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield has been a disaster for Palestinians. Hundreds of them have been killed, there has been widespread destruction of property and their would-be government has been partially dismantled.

Nevertheless, in Mr Arafat’s view, survival against the overwhelming strength of the Israelis amounts to a symbolic victory.

This was Mr Arafat’s third “last stand”. He survived the Israeli siege of Beirut in 1982 and the Syrian-backed Palestinian rebellion in Tripoli the following year. Each time he has emerged to fight another day.

His defiant words on the first day of the latest siege – “I want to be a martyr, a martyr, a martyr” – are repeated daily on Arab television channels. The question of Palestine is once again the burning international issue.

With his emergence from the siege, however, Mr Arafat may lose the aura of the Palestinian “symbol” and revert to being a deeply flawed temporal leader.

He may soon have to answer for any terrorist attacks that may take place against Israelis, for the deals he has had to make to secure his freedom, for the lack of progress towards Palestinian statehood and for the suffering of ordinary Palestinians.

In launching its operation, Israel had both political and military objectives: to neutralise Mr Arafat and to destroy the “infrastructure of terror”.

It looks as if it failed in the first aim, but can claim successes in the second.

Israel’s prime minister, Ariel Sharon, threatened to send Mr Arafat back into exile. But if the deal goes ahead as planned, the Palestinian leader will be allowed to move freely once again.

“Arafat’s personal standing was strengthened in the wake of Operation Protective Wall,” Maj Gen Aharon Zeevi, Israel’s head of military intelligence, told an Israeli Knesset committee this week in a frank assessment.

However, Israeli military commanders can claim concrete achievements against the militant networks.

Suicide bombings, which at one point were being carried out twice a day, have become much less frequent. It is still not clear, however, whether Israel has achieved a permanent success in its own war against terrorism, or merely a temporary respite.

The question is whether the end of the siege in Ramallah is a short-lived truce, or the beginning of a return to diplomacy. America has hinted at a joint diplomatic effort with Europe and the Arabs, in which Washington would push Israel towards compromise, while the rest would exert pressure on Mr Arafat.

Mr Sharon flies to Washington next week where he will discuss his plans for a regional conference of Israel and the Arab states.

But there is no obvious sign that the positions of either Mr Sharon or Mr Arafat have changed. The Israeli prime minister says he will agree to a Palestinian state on no more than half the West Bank. The Palestinians demand more than 96 per cent.

Unless there is a fundamental change in these positions, yesterday’s deal will turn out to be little more than brief pause in the duel between the two septuagenarian leaders.

“Pressure is now on Arafat to deliver peace”

DAILY TELEGRAPH – LONDON

03/12/2001

YASSER ARAFAT is, as ever, both the problem and the solution to the tragedy of the Middle East.

Anybody who has dealt with the Palestinian leader has found him infuriating, unreliable and mendacious.

Chaos has followed him to Jordan, Lebanon and, now, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Yet Mr Arafat may be the only person able to bring stability.

Last night, two questions were plaguing those grappling with the politics of the Middle East.

Does the Palestinian leader have the authority to restrain the militants? And is it possible ever to reach a peace agreement with him? The assumption underlying all peacemaking in the region is that the answer to both is “Yes”.

With a combination of pressure and inducements, it is thought, Mr Arafat could be made to lock up the extremists, enforce calm and end the conflict between Zionism and Arab nationalism.

The outbreak of the violence in September last year has convinced a growing number of Israelis that these were false hopes.

It was at the moment of maximum Israeli concessions at Camp David last year that Mr Arafat balked at declaring the end of the conflict.

There is little doubt that Mr Arafat has toyed with terrorism even after he formally abjured violence with the signing of the 1993 Oslo accords.

In an unequal negotiation with Israel, where the Jewish state has the military might and holds the territory under negotiation, Mr Arafat has maintained a deliberate ambiguity about terrorism.

At times he loosened the reins on Islamic militants to exert pressure on Israel; at other times he tightened his grip to demonstrate credibility with the international community.

With the start of the intifada, Mr Arafat’s Fatah movement joined in the attacks, at times in open co-ordination with Islamic Jihad. The Palestinian Authority formally condemned the most outrageous attacks, while its media kept up a steady stream of anti-Israeli incitement.

Cynical as it may seem, it is the violence of the intifada that has brought the question of Palestine back to the top of the agenda of Western leaders.

It is a sign of Mr Arafat’s tragic ability to miscalculate that he has allowed political violence to rob him of a favourable negotiating position.

At the very moment when Ariel Sharon is facing increased pressure from America, the suicide bombers have let him escape the demands for political concessions to the Palestinians.

Few can now answer Mr Sharon’s charge that Israel, like America, is waging a “war on terrorism”. The Palestinian Authority has become a “terrorist state” in the eyes of many Israelis.

If America can target Mullah Omar and the Taliban, why should Israel not have the right to sweep away Mr Arafat and his Palestinian Authority?

The West will make two arguments for sticking by Mr Arafat. First, the Palestinians are a stateless people and their homeland is under partial Israeli occupation. Getting rid of Mr Arafat will not solve the problem.

Second, there is no good alternative to Mr Arafat. There is no equivalent of Northern Alliance that can be helped to replace the Palestinian Authority.

The likely options – a chaotic break-up, or a re-occupation of the Palestinian autonomous enclaves – are worse from Israel’s perspective. Mr Arafat did once succeed in silencing the suicide bombers, in 1996.

Today the climate is radically different. Few Israelis trust Mr Arafat any longer. Palestinian society has been polarised by the conflict, and brutalised by Israeli reprisals and security measures.

A crackdown on terrorist groups raises the spectre of a Palestinian civil war and the possibility that the conflict could spill beyond Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Denis Ross, the American diplomat who for years travelled between Jerusalem, Gaza and Washington, believes that Mr Arafat does not have the mindset to sign a permanent peace.

But he believes that it is worth trying to reach a partial accord, and that is only possible with Mr Arafat.

“Arafat is weaker, but he can still stop the violence. He is still a symbol,” said Mr Ross last week.

“He is weaker than he was even a month ago. But if he waits for another month he will be even weaker.”

© Copyright of Telegraph Group Limited 2002.

– 26/06/2002

Medio Oriente di sangue: interviste e reportage

Si moltiplicano i libri dedicati alla disputa israelo-palestinese nel tentativo di comprendere le ragioni di un groviglio spesso difficile da districare. Tra questi libri, quello di Anton La Guardia, ex corrispondente per il ‘Daily Telegraph’ nel Medio Oriente, ha un titolo molto efficace “Terra santa, guerra profana” che già spiega, in parte, la situazione attuale. Oltre a ricordare i precedenti storici – spesso ignorati nelle ricostruzioni giornalistiche con il rischio di grossolani errori – La Guardia ha scelto come metodo quello di far parlare i diretti interessati. Ecco allora una serie di colloqui con gli israeliani più occidentalizzati e laici, i ragazzi ‘lanciasassi’ di Gaza, i nuovi nazionalisti religiosi ebraici, gli intellettuali palestinesi, le minoranze cristiane.

– 01/05/2002

Quella pace che nessuno sembra volere

Gli scarsi risultati della missione di Colin Powell, ogni giorno arriva un bollettino di eccidi e massacri su entrambi i fronti, corredato da reciproci scambi di accuse. Ormai il conflitto israeliano-palestinese sembra aver raggiunto il culmine. È una guerra in piena regola, che mette a rischio l’equilibrio della pace mondiale, già drammaticamente incrinato dalla catena di eventi seguiti all’ 11 settembre (e che non a caso ha scatenato paure e angosce il 18 aprile, con la vicenda del Pirellone). E la domanda chiave che, a questo punto, tutti si pongono, non solo i politologi, è : c’è ancora spazio per la diplomazia internazionale o si è già oltrepassata la soglia di non ritorno? Amica ne ha parlato con due esperti, ciascuno con una visuale diversa di un dramma che col passare dei giorni rivela implicazioni e sfaccettature sempre più complesse e allarmanti: Anton La Guardia, di origini italo-filippine che vive a Londra, autore di Terra santa, guerra profana, corrispondente da Israele tra il ’90 e il ’98 per il Daily Telegraph, e Fabrizio Vielmini, geo-politico torinese, studioso dell’Asia Centrale che ha scritto Il centro del mondo. Due secoli di manipolazioni del fondamentalismo islamico. I due saggi, editi da Fazi editore, escono a giugno. Dagli inizi del secolo scorso, la politica americana, ha svolto un ruolo determinante nel controllo del mondo. Quali effetti ha avuto nella questione mediorientale?

“Gli Stati Uniti sono stati il primo Paese a riconoscere nel 1948 lo Stato di Israele” risponde Anton La Guardia, “ma è solo dal ’67 che hanno cominciato ad appoggiarlo strategicamente. Nello stesso tempo, però, hanno enormi interessi anche nel mondo arabo. Quindi per loro è difficile svolgere un ruolo di mediazione”. Dello stesso parere, ma con una sfumatura più rigida è Vielmini. “La politica americana è contraddittoria. S’identifica totalmente col governo di Tel Aviv. Non può essere imparziale, anche per la potente lobby degli ebrei americani che difende Israele e che la arma, ma continua a presentarsi come giudice. Il segretario di Stato Colin Powell non può fare concessioni perché non ha questo mandato”.

Nei due saggi si ripercorre a tappe la storia del conflitto: in che modo si possono rintracciare le cause nel passato?

“La creazione dello Stato d’Israele ha due radici lontane”, spiega La Guardia. “Una risale all’oppressione degli ebrei in Russia e in Europa. Dalla Russia molti ebrei sono fuggiti in Palestina durante i pogrom del 1881, e hanno creato le prime colonie agricole. Poi sono entrati in gioco gli schemi imperialistici britannici che hanno concesso agli ebrei la Palestina. Ma la Palestina non era una terra vuota, bensì popolata con una forma di protettorato sotto l’egida britannica. Nell’ottica occidentale, dunque, la Palestina era un territorio da colonizzare”.

“Quando la Gran Bretagna si è ritirata dalla fascia di territori che va dall’India al Medio Oriente, ha creato un sistema di attori contrapposti, ognuno impossibilitato a prevalere sull’altro. Il classico divide et impera”, continua Vielmini. In questo meccanismo si è inserita la politica Israeliana. Israele non ha mai smesso di allargarsi. Dalla caduta dell’Urss in poi si è trapiantato più di un milione di nuovi cittadini. E oggi, dopo il tracollo economico, sembra che stia per arrivare una decina di migliaia di ebrei dall’argentina. Ma non si tratta solo di una colonizzazione a macchia d’olio. I coloni si impadroniscono delle sorgenti, ghettizzano i palestinesi dei dintorni, li espropriano delle proprie risorse territoriali. Naturalmente non è da mettere in discussione l’esistenza dello Stato d’Israele ma la politica folle delle colonie che poi è la politica del premier Ariel Sharon. Non c’è la volontà di risolvere il conflitto. Israele vive principalmente con i milioni di dollari che arrivano nei suoi forzieri giustificati dallo stato di guerra”. L’Unione europea avrebbe potuto influire sulla soluzione pacifica del conflitto? “Quale Europa? Romano Prodi, Tony Blair? Chi parla per l’Unione europea?”, si domanda scettico La Guardia. “Certo, l’Europa potrebbe usare leve economiche, ma non ha alcuna influenza strategica-militare. Al massimo, può appoggiare la politica americana”. Vielmini è, invece, convinto dell’importanza del ruolo europeo: “Se l’Europa bloccasse tutti gli accordi economici, Israele sarebbe costretta a venire a patti”. Ma c’è ancora la possibilità di un dialogo a medio o almeno a lungo termine? “Le posizioni sono così polarizzate che sarà difficile un dialogo nel medio termine”, risponde pessimista La Guardia. “Si dovrà tornare alla soluzione della spartizione dei territori prospettata alla fine del 2001: un accordo speciale su Gerusalemme, il ritorno dei rifugiati palestinesi in Plaestina ma non in Israele e scambi territoriali per ripagare i palestinesi. Inoltre la comunità internazionale dovrebbe esprimere un criterio di giustizia per permettere ai moderati di ogni parte di rinforzarsi”. Per Vielmini “l’unica via d’uscita è, oltre al blocco economico per Israele, una forza europea internazionalmente riconosciuta che si disponga lungo la frontiera e impedisca alle forze israeliane di estendere il raggio d’azione”. Il parere di entrambi sui paesi arabi è negativo. “Nella situazione attuale anche i Paesi più moderati temono le reazioni della gente che vuole la guerra” spiega La Guardia. Incalza Vielmini: “Hanno fatto una pessima figura. Il piano saudita, per esempio, si è infranto senza aver ottenuto nulla.

Probabilmente sono stati commessi errori dalle grandi potenze dopo la Seconda guerra mondiale. Quali possono essere stati? “Dopo le persecuzioni avvenute in Europa, tutti gli occidentali hanno convenuto che fosse giusto dare agli ebrei un loro stato”, risponde La Guardia. “Ma gli arabi giustamente dicono: “perché dobbiamo pagare per le colpe degli europei?”. Quindi la situazione era già pregiudicata alle origini. Il grave errore è stato nel non aver impostato una strategia”. Secondo Vielmini “Quello che è stato messo in piedi nel dopoguerra è un sistema che si basa sulla conflittualità costante, un disordine sistematico e azionabile come quello del Pakistan e del Kashmir”. Gli israeliani vogliono costruire una sorta di muro-reticolato lungo la Cisgiordania. Non è pericolosamente simile al Muro della vergogna di Berlino? “Ma qual è la frontiera?”, si domanda La Guardia. “Qualsiasi cosa interpongano, lasciano 200 mila coloni dentro la Cisgiordania che è lunga qualche centinaio di chilometri. Anche per Vielmini è una cosa irrealizzabile. “Le colonie, grossi insediamenti collegati con strade asfaltate, sono disposte a macchia di leopardo”, dice. I kamikaze sono considerati dall’Occidente terroristi a tutti gli effetti. È un’interpretazione giusta o il fenomeno va visto in un’ottica più complessa? “I palestinesi con i loro atti di terrorismo continuano a mandare agli israeliani il messaggio che non vogliono la pace” è drastico La Guardia, ma aggiunge: “Capisco la logica dei palestinesi, gli israeliani sono più forti di noi e noi ricorriamo a una specie di equilibrio del terrore. Loro sentono il dolore che sentiamo noi. Se riusciamo a mietere più vittime, pensano, gli israeliani si ritireranno. Il problema gravissimo è che non distinguono fra bersagli militari e civili”. Vielmini, invece, non li definirebbe terroristi. “I gruppi di Hammas, finanziati dall’esterno, lo erano. Oggi il movimento mi sembra una resistenza ad un’occupazione. Ci sono decine di migliaia di giovani che crescono nei ghetti senz’acqua, circondati dai fili spinati delle strade che portano alle belle case dei coloni, e che arrivano a livelli di degradazione umana tale che farsi saltare in aria è un atto quasi liberatorio”. Un giudizio su Arafat? Per La Guardia “Ha sempre giocato in penombra, senza fermare il terrorismo”. Per Vielmini: “È un uomo vecchio, in balia degli eventi e le sue capacità sono ormai limitate. Ma resta la figura più positiva. Ha cercato di avviare il dialogo, quel dialogo che Sharon ha rifiutato.